Crispus Attucks: American Martyr

It was a cold night in March of 1770. On King Street in Boston, Massachusetts a street brawl was brewing that would become one of the bloodiest slaughters in American history. The agitation had been building for years among the colonist. Maybe they wondered how a King 3,000 miles away had so much power over their existence. With 4,000 British soldiers in a city with only 17,000 citizens, the military presence was intense. Maybe Britain thought that if colonists couldn’t be content—intimidation would work just as well.

Military occupations are always a strange state of affairs. Sitting in the grey area between war and peace, and somewhere between conflict and resolution. So for colonist to look out their window daily and see British troops caused a deeply hostile frustration.

That night a riotous group of Bostonian dockworkers led by Crispus Attucks made their way to the customs house. This was where King George’s money was stored and there stood private Hugh White as the only soldier guarding it.

He may have been surprised or maybe thought business as usual. Belligerent Bostonians clashed with British soldiers regularly. Or maybe he sensed this was something different. This group wouldn’t relent. They hurled insults. Threatened violence. Their voices grew from isolated insults to angry yells.

Some of them were inches from him. In all the commotion, white cracked a colonist in the head with the butt of his rifle. They retaliated. Pelting him with tightly packed snowballs. The town bells rang out cutting through the night air—normally reserved for fires— this time for a different emergency. More colonists rush out to view the spectacle.

White panicked and called for reinforcements. Captain Thomas Preston arrived with 6 other soldiers and took up defensive positions with White. They shouldered their muskets along with the heavy burden of making momentary life or death decisions. The colonists —who were armed with sticks and clubs— make threats and grabbed at the soldiers’ weapons. “Come on you bloody backs.” You lobster scoundrels, fire if you dare!” Crispus Attucks lunged forward. Some yell “hold your fire.” Then 6 or 7 shots crack the night air like the sound of a leather whip snapping under a fast hand.

When the smoke cleared there were 5 colonists were dead. 6 wounded. Crispus Attucks was the first among them.

John Haley Bellamy, Carved Eagle with Two Draped Flags Under a Center Shield, ca. 1872–1890. Photography by David Bohl. Though America was not yet a nation in 1770, the American spirit of liberty blew through the colonies like a fierce wind.

WHO WAS CRISPUS ATTUCKS

Crispus Attucks is forever known as the first casualty in the American revolution. Symbolized as a martyr, glorified as a patriot, and held up as a standard for citizenship and sacrifice. Ironic because these are attributes not often associated with a black man born in the 18th century.

We don’t know a lot about Crispus Attucks. His life story—like an unfinished masterpiece of a long-gone artist—longs to be completed, and never will be. He was born of African and Native American descent. His mother was thought to be of Algonquin descent— those Eastern woodland natives who had prospered in the region for centuries. tribe. Native descent. His father was thought to be a slave originally from —we’ll sadly never know, but somewhere on the continent of Africa.

Born about 20 miles west of Boston —one key piece of information provides us with an invaluable clue as to who this man was. An escaped slave ad. So we see his first act of liberation wasn’t to free America from Britain but to free himself from America’s slave system. The put out October 2nd, 1750 read:

“

RAN-away from his Master William Brown of Framingham, on the 30th of Sept. last, a Mulatto Fellow, about 27 Years of Age, named Crispas, 6 Feet two Inches high, short curled Hair, his Knees nearer together than common; had on a light colour’d Bearskin Coat, plain brown Fustian Jacket, or brown all-Wool one, new Buckskin Breeches, blue Yarn Stockings, and a check’d woollen Shirt.

Whoever shall take up said Run-away, and convey him to his above said Master, shall have ten Pounds, old Tenor Reward, and all necessary Charges paid. And all Masters of Vessels and others, are hereby cautioned against concealing or carrying off said Servant on Penalty of the Law. ”

— BOSTON GAZETTE - OCTOBER 2, 1750

Think of history in modern terms, and sometimes it proves difficult. I try to imagine going on Facebook or Instagram and one of the annoying ads that popped up was for a fugitive slave, it’s unthinkable. Yet only a few generations of ads like this in local papers were completely normal. Yet, we know much of what we know about Attucks is through an ad like this, and as well see people have filled in the gaps with what they don’t know.

The legacy of Crispus Attucks is exemplary or cautionary, depending on who is telling his story. Abolitionist and civil rights activists wrapped his memory in the cape of universal freedom and civil liberty. Proudly proclaim he was the first African American to die for America. As though his life is an evergreen example that we’ve always fought, bled, and died for this country since its very birth. Dr. Martin Luther King jr. said:

“He is one of the most important figures in African-American history, not for what he did for his own race but for what he did for all oppressed people everywhere. He is a reminder that the African-American heritage is not only African but American and it is a heritage that begins with the beginning of America.”

— DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.

Contrast this with the view of him by black separatists. Or leaders of the black power movement in the mid-’60s like Stokely Carmichael. They called him a fool, and a sell-out. Fighting for a country that would reduce him to a slave. In a speech in 1967, he said:

“The very first man to die for the War of Independence in this country was a black man named Crispus Attucks! The very first man, yes! [Applause]

He was a fool! Yeah! [Shocked Applause]

He died for white folk country while the rest of his black brothers were enslaved in this country. He should’ve been fighting white folk instead of dying for white folk! But that’s been our history as black people—we’ve always been dying for white folk!”

— STOKELY CARMICHAEL

Here we see that history is like clay. Molded and reshaped by new potters every generation, and sometimes reshaped in the present. Forever being stretched, thinned, and directed by whoever is interpreting and telling the story. Attucks life is no exception.

THE BOSTON MASSACRE

As you can imagine, things weren’t going well in the years leading up to the Boston Massacre. Enough colonists hated the imperial army's military occupation to clash with them regularly. Unfair taxes was one headache. But even greater, Boston was a harbor city full of sailors who had a legitimate grievance with the British. Impressment. The legal practice of being forced to labor on a British sea vessel. Legal kidnapping is what it was. There were impressment officers and impressment gangs. They would walk up to working seamen, whose homes and lives were in Boston, and force them to work on their vessels.

These were wild times. Gangs of men running around with clubs, knives, and cutlasses. Many assaulting and insulting soldiers. Many were kidnapped and forced into labor. Civil disobedience.

Boston is ground zero for revolution. In 1765 there was a major riot. A kid named Christopher Cider was shot above the eye and killed, he was only 11 years old. Colonists against British loyalists. Boycotting British goods. Shot for throwing a rock and shattering the glass of the store of a British loyalist. 5,000 Bostonians attended the funeral. Paid for by Samuel Adams. His death was used as propaganda to push the patriotic cause. Attucks was a part of this world abuzz with revolt and revolution. He was there. Aware of the freedom and liberty talk. So it may not be a stretch to say that he bought into it leading up to his last fateful day.

The Bloody Massacre. Paul Revere. Boston, Massachusetts 1770. There are many fascinating things about this photo which is only loosely based on the facts of what happened. Revere published this as a piece of propaganda—clear in his intent to demonize the British and push colonist to identify with a patriotic cause. Maybe this is why in many versions including this one Attucks is depicted as white. Or why the soldiers appear as though they are lined up and being ordered to fire, instead of the disorganized chaos that really happend. Look closely at the soldiers faces, they even look as though they enjoy the violence.

The Bloody Massacre. Paul Revere. Boston, Massachusetts 1770. There are many fascinating things about this photo that are only loosely based on the facts of what happened. Revere published this as a piece of propaganda—clear in his intent to demonize the British and push colonists to identify with a patriotic cause. Maybe this is why in many versions including this one Attucks is depicted as white. Or why do the soldiers appear as though they are lined up and being ordered to fire, instead of the disorganized chaos that really happened. Look closely at the soldier’s faces, they even look as though they enjoy the violence.

FIRSTHAND ACCOUNTS

There are many firsthand accounts of the Boston Massacre. Many of which come out of the trial of the British soldiers indicted for murder.Benjamin Burdick's testimony:

“When I came into King Street about 9 o’Clock I saw the Soldiers round the Centinel. I asked one if he was loaded and he said yes. I asked him if he would fire, he said yes by the Eternal God and pushed his Bayonet at me. After the firing the Captain came before the Soldiers and put up their Guns with his arm and said stop firing, don’t fire no more or don’t fire again.

I heard the word fire and took it and am certain that it came from behind the Soldiers. I saw a man passing busily behind who I took to be an Officer. The firing was a little time after. I saw some persons fall. Before the firing I saw a stick thrown at the Soldiers. The word fire I took to be a word of Command. I had in my hand a highland broad Sword which I brought from home. Upon my coming out I was told it was a wrangle between the Soldiers and people, upon that I went back and got my Sword.

I never used to go out with a weapon. I had not my Sword drawn till after the Soldier pushed his Bayonet at me. I should have cut his head off if he had stepped out of his Rank to attack me again. At the first firing the People were chiefly in Royal Exchange lane, there being about 50 in the Street. After the firing I went up to the Soldiers and told them I wanted to see some faces that I might swear to them another day. The Centinel in a melancholy tone said perhaps Sir you may.”

This was the testimony of a colonist. Think about this like a lawyer or prosecutor trying the case. Then comes the testimony of Captain Thomas Preston a British soldier:

“The mob still increased and were outrageous, striking their clubs or bludgeons one against another, and calling out “Come on you rascals, you bloody backs, you lobster scoundrels, fire if you dare, God damn you, fire and be damned, we know you dare not”, and much more such language was used. At this time I was between the soldiers and the mob, parlaying with and endeavoring all in my power to persuade them to retire peaceably, but to no purpose.

They [the civilians] advanced to the points of the bayonets, struck some of them and even the muzzles of the pieces, and seemed to be endeavouring to close with the soldiers. On which some well behaved persons asked me if the guns were charged. I replied yes. They then asked me if I intended to order the men to fire. I answered no, by no means, observing to them that I was advanced before the muzzles of the men’s pieces, and must fall a sacrifice if they fired; that the soldiers were upon the half cock and charged bayonets, and my giving the word fire under those circumstances would prove me to be no officer.

While I was thus speaking one of the soldiers, having received a severe blow with a stick, stepped a little to one side and instantly fired… On this a general attack was made on the men by a great number of heavy clubs and snowballs being thrown at them, by which all our lives were in imminent danger… some persons at the same time from behind calling out “Damn your bloods, why don’t you fire”. Instantly three or four of the soldiers fired… On my asking the soldiers why they fired without orders, they said they heard the word ‘fire’ and supposed it came from me. This might be the case as many of the mob called out fire, fire, but I assured the men that I gave no such order… that my words were “don’t fire, stop your firing.”

Two sides to every story were the case of the century. Surprisingly, future president John Adams worked as an attorney for the British. Why? We don’t know. Loyalty to the British? A fair trial for the soldiers? Imagine the retaliation of the British crown had they put these soldiers to death. Maybe Adams was trying to be a diplomat.

The Boston Massacre, ca. 1868. by Alonzo Chappel - This deception of the Boston massacre shows the cruel chaos that falls more in line with the firsthand accounts. Crispus Attucks appears bravely on the front lines in this picture.

Would the soldiers be proven innocent in an act of self-defense or did the colonists have a legitimate claim to fight?

John Adams makes his arguments and in them takes direct aim at Crispus Attucks as the true aggressor:

“When the multitude was shouting and huzzaing, and threatening life, the bells all ringing, the mob whistle screaming and rending like an Indian yell, the people from all quarters throwing every species of rubbish they could pick up in the street, and some who were quite on the other side of the street throwing clubs at the whole party, Montgomery in particular, smote with a club and knocked down, and as soon as he could rise and take up his firelock, another club from a far struck his breast or shoulder, what could he do?

Do you expect he should behave like a Stoic Philosopher lost in Apathy? Patient as Epictetus while his master was breaking his legs with a cudgel? It is impossible you should find him guilty of murder. You must suppose him divested of all human passions, if you don’t think him at the least provoked, thrown off his guard, and into the furor brevis, by such treatment as this.

Bailey “Saw the Mulatto seven or eight minutes before the firing, at the head of twenty or thirty sailors in Corn-hill, and he had a large cord-wood stick.” So that this Attucks, by this testimony of Bailey compared with that of Andrew, and some others, appears to have undertaken to be the hero of the night; and to lead this army with banners, to form them in the first place in Dock square, and march them up to King-street, with their clubs; they passed through the main-street up to the Main-guard, in order to make the attack. If this was not an unlawful assembly, there never was one in the world.

Attucks with his myrmidons comes round Jackson’s corner, and down to the party by the Sentry-box; when the soldiers pushed the people off, this man with his party cried, do not be afraid of them, they dare not fire, kill them! kill them! knock them over! And he tried to knock their brains out. It is plain the soldiers did not leave their station, but cried to the people, stand off: now to have this reinforcement coming down under the command of a stout Mulatto fellow, whose very looks, was enough to terrify any person, what had not the soldiers then to fear? He had hardiness enough to fall in upon them, and with one hand took hold of a bayonet, and with the other knocked the man down: This was the behavior of Attucks;— to whose mad behavior, in all probability, the dreadful carnage of that night, is chiefly to be ascribed. ”

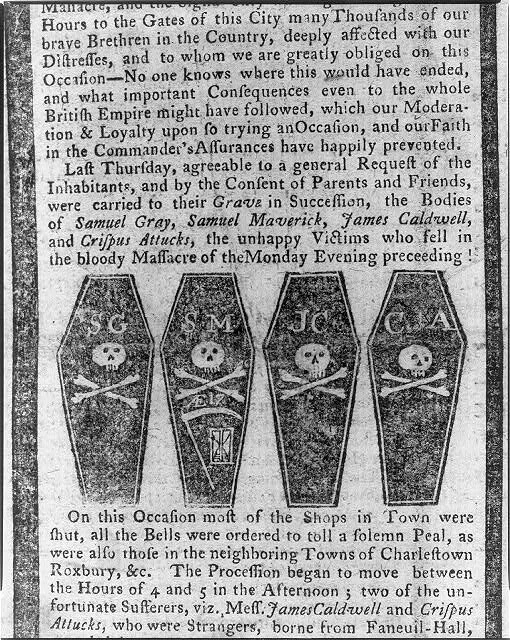

Obituary showing the name of Crispus Attucks and the other causalities of the Boston massacre.

Obituary showing the name of Crispus Attucks and the other causalities of the Boston massacre.

John Adams is often praised as a progressive in his era as he was one of the founding fathers against slavery. Yet, I could’’t help but get a strong sense of deep prejudice when reading his arguments placing all the blame on Attucks. Clearly stating that if not for this Mulatto man—all the violence, all the drama, all the turmoil would’ve been avoided. This scary mulatto boogeyman was made the scapegoat.

The jury acquitted six of the soldiers including Hugh White, who were found not guilty of murder but guilty of manslaughter and escaped the death penalty

Firsts are significant. Everyone loves first. You're firstborn. Your first love. Your first car. Crispus Attucks was the first to die in what became the Revolutionary war. Was Attucks a patriot? Was he challenging the British soldiers for the liberation of the colonies?

We may never know.

We do know that he valued freedom as an escaped slave. So it may not be far-fetched to think he saw a common bond between the liberation of black people and the liberation of the colonies from British rule. We do know he is a major figure in American folklore. Praised for his heroism. His death is seen as a challenge to imperialism and oppression.